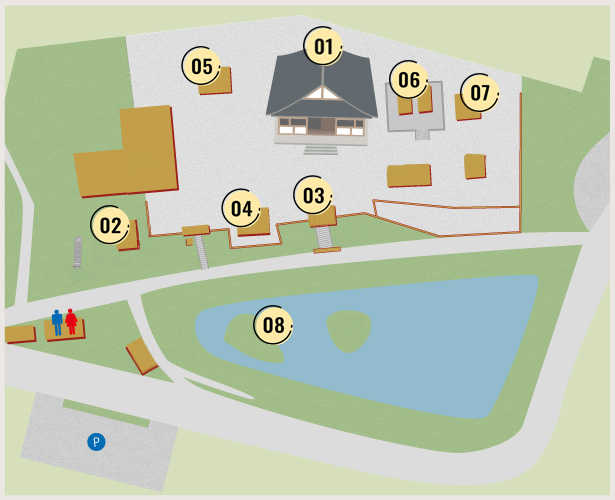

Temple Grounds Guide

01.Main Hall

The Main Hall was destroyed in a fire along with most of Enjōji Temple in February 1467, at the onset of the Ōnin War. Reconstruction began the month afterward. It was rebuilt swiftly in the exact style and size as the original hall from the late Heian period (794–1185), including the stage-like sections that flank the hall’s stairs.

Inside the Main Hall is Enjōji’s principal image, a statue of Amida Buddha from 1112. Surrounding the statue are four pillars painted with the 25 bodhisattvas who accompany Amida Buddha when he descends to take the deceased to the Pure Land, a realm free from suffering. The metal bases that affix the pillars to the floor are remnants from the original hall.

The hall’s spacious design allows temple-goers to perform Amida zanmai, a form of prayer in which one repeatedly chants Amida Buddha’s name while circling his statue; reciting the name of Amida is believed to guarantee rebirth in the Pure Land. The surrounding rooms contain Buddhist statuary, including a statue of Eleven-Headed Kannon, which was the temple’s original principal image, as well as various artifacts and historical records.

This statue of Amida Buddha has been the principal image of Enjōji Temple since 1112. Amida is a popular deity in the Mahayana tradition of Japanese Buddhism. He is said to guarantee rebirth in the Pure Land, a realm free of suffering, to those who invoke his name.

The soft lines of the body, the tranquil expression, and the delicate, childlike face of this Amida exemplify the style of statuary dominant in the late Heian period (794–1185). The hands form the meditation mudra, which symbolizes the triumph of enlightenment over illusion. Amida’s eyes are half-open and look slightly downward, indicating that he has descended to greet the deceased and escort them to his Pure Land.

The statue is backed by an openwork mandorla in which light radiates out from Amida Buddha in an intricate pattern. Late-Heian mandorlas are quite rare, and very few survive in such pristine condition. The statue sits on a pedestal that resembles the imperial throne, an unusual feature for a Buddhist statue.

Surrounding Amida Buddha are the Four Heavenly Kings, the guardians of the four cardinal directions. Dressed in armor and carrying weapons, these kings are believed to ward off evil and can be found in most Buddhist temples in Japan. Their frightening faces and dynamic poses emphasize their protective role and distinguish them from the more serene statues of buddhas and bodhisattvas.

These statues are made of Japanese cypress. The dynamic twisting of their bodies and the detailed folds and patterns of the armor display the realistic style of statuary of the early Kamakura period (1185–1333). The brilliant colors and patterns that once decorated the statues are visible in places, showing hints of their original glory.

According to an inscription inside its base, the statue of Jikokuten dates to 1217. Jikokuten is the King of the East and stands in front of the other guardians on Amida’s left. The statue’s powerful features, which resemble the style of the Kei school of Buddhist art, have led to theories that this is the work of Keishō (dates unknown), the fourth son of the master sculptor Unkei (1150–1223).

02.Sououden

National Treasure

This statue of Dainichi Buddha is the earliest known work by the master sculptor Unkei (1150–1223), who was only 25 years old at the time. An inscription by Unkei on the statue’s base reveals that it was commissioned on November 24, 1175, and completed on October 19, 1176. Unkei even recorded that he received 43 rolls of fine silk as payment. The length of time he devoted to the work and the unusually detailed inscription may indicate Unkei’s enthusiasm for what was likely his first commissioned statue.

The statue displays early signs of the realism that came to define Unkei’s artistic style, such as a sense of vigor in the elasticity and fullness of its body. The eyes glitter in the light, an effect made possible by affixing crystals behind them, inside the statue’s head. Dainichi’s hands form the “knowledge-fist” mudra, which symbolizes the sharing of the Buddha’s wisdom with all living beings.

Buddhas are usually depicted in simple robes like those said to be worn by Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha. Dainichi Buddha, however, has lavish jewelry, including a crown, necklace, and arm bands. These ornaments are attributes of ancient Indian royalty. This difference in attire is believed to indicate Dainichi’s special position in Shingon Buddhism, in which he represents the truth of the universe and oversees all realms of existence as the Cosmic Buddha.

03.Rōmon Gate

This rōmon gate was erected two years after the original gate and most of halls of Enjōji Temple were burned down during the Ōnin War (1467–77). Like all rōmon gates, it has a false second story. However, several common features, such as a decorative balustrade, doors, and slatted windows, are missing. In addition, this gate was not painted vermilion and retains the natural color of its cypress bark.

Notice the ornate hanahijiki brackets that sit directly above both sides of the doorway. Such brackets emerged in the late Kamakura period (1185–1333) and come in an array of designs. The bracket seen upon entering the temple is carved with lotus flowers, whereas the one seen upon exiting features a peony topped with a sacred gem. The minute details of these brackets testify to the skill of the artist, as well as the grand vision of the restored gate’s design.

04.Tahōtō Pagoda

This is a tahōtō (lit. “many-jeweled pagoda”), a two-story structure found in many Esoteric Buddhist temples. It was originally built around 1176 to house a statue of Dainichi Buddha by the master sculptor Unkei (1150–1223). After Unkei’s statue was designated a National Treasure and moved to Sō’ōden Hall for preservation, a faithful replica of the statue was enshrined here in its stead.

The replica was sculpted by Fujimagari Takaya (b. 1982), a graduate student from the Tokyo University of the Arts. Fujimagari reproduced the original statue using the same historical techniques and tools as Unkei, providing a glimpse of what Unkei’s statue may have originally looked like. The statue’s rich and colorful ornamentation challenges contemporary perspectives of Buddhist statuary as fundamentally austere.

This Tahōtō Pagoda is the third iteration of the structure. The first was destroyed by warfare in 1467, and the second was moved to Chōjūji Temple in Kamakura in 1920. The current pagoda was built in 1986. Its doors remain open throughout the year, allowing visitors to freely view the statue of Dainichi Buddha.

05.Goma Hall

This hall is dedicated to goma, an ancient Indian fire ritual practiced in esoteric Buddhist sects such as Shingon. In these ceremonies, monks burn wooden tablets inscribed with individual prayers, symbolizing the burning of defilements and negative emotions that poison the mind. Inside the hall are statues of three significant figures: Kūkai, the founder of Shingon Buddhism; Monju, the bodhisattva of wisdom, depicted as a monk; and Fudō Myōō, the Immovable Wisdom King.

The statue of Monju on the left originally sat in Enjōji Temple’s refectory, where the monks would eat their meals. It symbolized the intake of wisdom along with food. In the center is Fudō Myōō, who is surrounded by the purifying flames of wisdom. As the principal deity of goma, his statue is commonly found in halls dedicated to the ceremony.

Like many Shingon temples, Enjōji holds a goma ritual on the 28th of each month, the day dedicated to Fudō Myōō.

06.Kasuga and Hakusan Shrines

National Treasure

These small shrines originally were part of Kasuga Taisha Shrine in central Nara. Every 20 years, the inner sanctuary of Kasuga Taisha is ceremonially rebuilt, and the old structures are donated to nearby shrines and temples. This tradition has continued for over 1,000 years, and the Kasuga shrines at Enjōji are the oldest examples of these donations.

When these shrines came to Enjōji, they were installed to venerate Shinto deities and help protect the temple. It is not unusual for Shinto elements to appear in Buddhist temples, as the two religions have shared a close relationship for most of Japanese history. The shrine on the left is dedicated to Kasuga Daimyōjin and the shrine on the right to Hakusan Daigongen. Both are collective names for Shinto and Buddhist deities who have been enshrined as a single entity. Kasuga Daimyōjin is worshipped at Kasuga Taisha, and Hakusan Daigongen is believed to reside on Mt. Hakusan in central Japan.

Wooden plaques inscribed with records of previous repairs were discovered inside the shrines in 1916, revealing that the earliest repair work was completed in 1494. This information, coupled with stylistic analysis of the architecture, suggests that the shrines were likely constructed in the early Kamakura period (1185–1333). If so, this would make Kasuga and Hakusan Shrines the oldest examples of the eponymous kasuga-zukuri architectural style, which features large gabled roofs topped with forked finials.

07.Ugajin Shrine

This is a shrine that venerates Ugajin, an ancient Shinto deity of music and the arts. Ugajin is depicted with the head of a human being, either male or female, and the body of a white snake. Benzaiten, a Hindu goddess who was adopted into Buddhist and Shinto traditions, shares many traits with Ugajin. For example, Benzaiten is not only a goddess of music and the arts, but also a powerful water deity associated with snakes. These common attributes eventually led to Ugajin and Benzaiten’s veneration as a single deity called Uga Benten or Uga Benzaiten.

Similar to the Kasuga and Hakusan Shrines nearby, this shrine was built in the kasuga-zukuri style of Kasuga Taisha Shrine. Its roof, however, has bargeboard that curves in the center before straightening at the ends. This is known as a karahafu roof, an innovative style that emerged in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). This is the oldest example of a karahafu roof in Nara Prefecture.

08.Enjōji Temple Garden

Enjōji Temple’s garden was designed under the direction of the monk Kanpen (1100–66), who is said to have based its shape on the Sanskrit seed syllable “ban.” This syllable represents the Cosmic Buddha Dainichi, the primary deity of Shingon Buddhism.

Enjōji’s garden is one of few remaining examples of a shinden-style garden, which was a popular feature in aristocratic residences of the Heian period (794–1185). Like other shinden gardens, its large central pond is fed by an artificial stream and contains small islands. The largest of these islands was once connected to the pond’s north and south shores by two arched bridges.

Unfortunately, the garden’s natural scenery was marred when the pond was filled in and bisected by a prefectural road in the early Meiji era (1868–1912). Nearly a century later, the road was moved further south, and in 1975, the pond was excavated and restored to its original shinden style. Today, Enjōji’s historic garden offers a valuable look into the aesthetics of twelfth-century aristocrats.